This post is based on a talk given about the paper Privacy Legislation as Business Risks: How GDPR and CCPA are Represented in Technology Companies’ Investment Risk Disclosures by Richmond Y. Wong, Andrew Chong, and R. Cooper Aspegren, published in the Journal Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Volume 7 Issue CSCW1, and presented at the 2023 ACM Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) Conference. [Download the full paper]

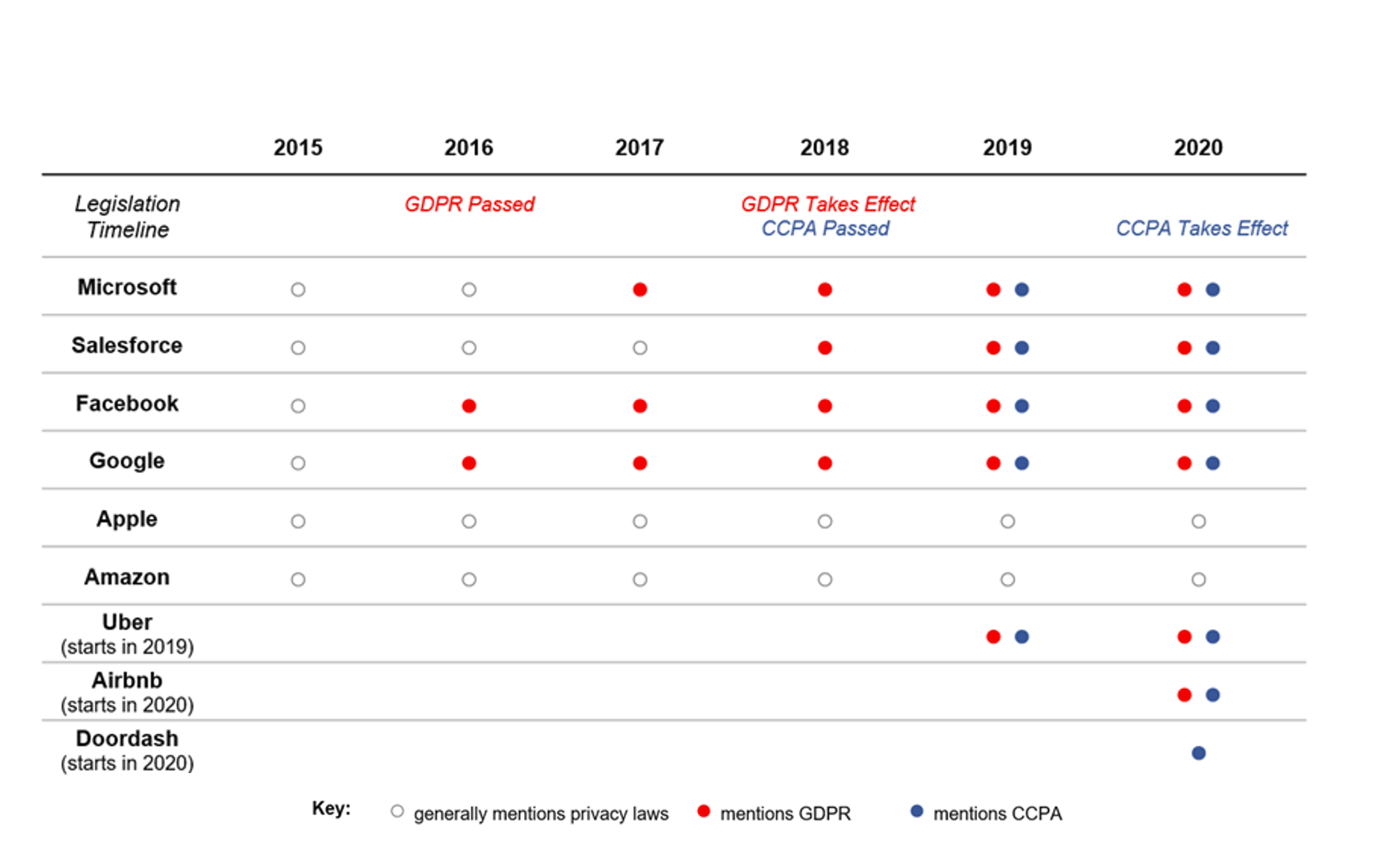

In recent years, concerns of consumer data privacy has been addressed by the passage of new legislation including the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in 2018 (which has since been superseded by the California Privacy Rights Act). In this paper, we wanted to understand how technology companies begin to view and frame issues related to these privacy laws when talking to investors. So we analyzed annual regulatory financial reports that publicly traded companies in the U.S. must file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

As background for this work, we’re shifting away from HCI’s dominant conception of data privacy as a user decision-making problem, and instead we’re looking at data privacy as a problem of power by the institutions that make technologies. Privacy scholars Seda Gürses and Joris van Hoboken argue that in addition to user perspectives, we also need to understand privacy as it relates to the context of technology production:

inquiries into [technology] production can help us better engage with new configurations of power that have implications for fundamental rights and freedoms, including privacy

Gürses and Van Hoboken 2017

And we build on the work of Nora McDonald and Andrea Forte who analyze how social media companies’ own blog posts create narratives around identity and construct particular ideas about what privacy is on their platforms.

One of our motivations of looking at this is that prior work has shown the limitations of user-centered arguments for making progress on social values and ethical issues within tech companies, such as privacy. For instance, in an enterprise business, user-centered arguments to protect privacy might not be convincing to mangers and decision-makers because their clients are other organizations, not end users. Product design decisions often reflect financial incentives that organizations have, which may not necessarily be the same as what is “good for the user.”

So we want to focus on how technology companies construct narratives about data privacy laws when communicating with a different audience: current and potential investors. We think about practices of financial investment and corporate shareholding as forms of infrastructure that allow technology platforms to operate. We also think about these practices as a place where the social values of tech development (such as privacy) can be contested. There’s a lot of practices involved in corporate finance, but we look closely at the discourse within one particular practice: annual regulatory filings.

Looking at Form 10-K’s Filed with the Security and Exchange Commission

Publicly traded companies in U.S. are required to file a form 10-K annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission, a regulatory agency. These documents are publicly accessible – the image above shows an example of a coversheet for a Form 10K from Microsoft in 2020. The idea is that through these disclosures, investors can make informed decisions about their investments. A Form 10-K includes 15 sections that disclose information including: the company’s business practices, financial data, and potential business risks. We look specifically at the sections that discuss potential risks that companies face, which is listed in Item 1A, Risk Factors. This section generally qualitatively describes the nature of risks, but does not always include a description of how the company is addressing that risk.

The image above shows what a risk factor looks like. There’s a bold statement that describes a risk factor, and below that statement is additional text describing that risk factor. This is from Google in 2015. The bolded statement says: “we generate a significant portion of our revenues from advertising, and reduced spending by advertisers or a loss of partners could seriously harm our business.” The Risk Factors section is often anywhere from 10 to 30 pages of these types of paragraphs. It may sound like a lot of dry reading, but we found lots of things that we found interesting!

We decided to focus on large technology companies that produce platforms for online collaboration, work, communication, and social activity. We aimed to curate a sample of companies that would capture breadth and diversity, rather than a complete accounting or a statistically representative sample. We looked at 9 companies’ filings. Given that the GDPR was passed in Europe in 2016,and the CCPA was passed in 2018, we looked at the Form 10-K’s from between 2015-2020. We did multiple rounds of qualitative coding to understand the language used when companies mention the GDPR, CCPA, or privacy in a risk factor. We looked at the context of that risk and the stated impacts to the company based on the risk. The chart below shows the companies we looked at. The open circles are years companies mentioned privacy laws generically in their risk factors; red dots are years they mentioned the GDPR; blue dots are years they mentioned the CCPA.

Findings

We found that companies framed business risks from the GDPR, CCPA, and privacy laws in 5 major ways:

- Regulatory Risks: This is the obvious things we think of when there’s a law or regulation.What are the direct penalties and legal consequences the company might face if they violate a law?

- Brand and Reputational Risks: How do the laws indirectly affect the company’s brand and reputation?

- Risks related to Internal Business Practices: How do the laws affect the company’s ability to conduct business and develop its products?

- Risks Related to External Stakeholders and Ecosystems: How do the laws affect relationships with stakeholders outside of the company? Are companies now liable for things their partners or vendors do?

- Cybersecurity Risks: How do the laws affect the company’s cybersecurity practices?

The paper has more detail about all five of these framings, but below I’ll provide a little more detail about brand and reputational risks, and risks related to external stakeholders.

Brand and Reputational Risks

Citing the GDPR and CCPA as a brand and reputational risk shows a really interesting indirect effect of data privacy laws. Basically it might be a small reputational problem to a company if some individuals feel like a company is violating their privacy; but it might be a much larger reputational problem if it is known that a company violated a law about privacy, perhaps because it suggests the company has violated a societal agreement.

In 2018 Microsoft, Google, Facebook and Salesforce all added new language discussing how violating the GDPR could create reputational risks. Google wrote: “If our operations are found to be in violation of the GDPR’s requirements, we may […] be subject to significant civil penalties, business disruption, and reputational harm, any of which could have a material adverse effect on our business.” These framings of brand and reputational risk stem from the potential negative publicity that could result from the public attention of being investigated or being found in violation of the new laws.

Risks Related to External Stakeholders and Ecosystems

Companies also discussed how privacy legislation might create risks in their relationships with external stakeholders outside the company, including users, enterprise clients, contractors, or third-party developers.

Several companies described business risks stemming from their own users’ exercising new privacy rights. In 2020, Facebook wrote:

In particular, we have seen an increasing number of users opt out of certain types of ad targeting in Europe following adoption of the GDPR, and we have introduced product changes that limit data signal use for certain users in California following adoption of the CCPA.

Facebook Form 10-K, 2020

Facebook noted how these changes negatively impacted their ability to target and measure ads, and negatively impacted their advertising revenue. Here, users exercising their new data protection rights were framed as a business risk.

Some companies, particularly gig economy companies, also described privacy tradeoffs among different groups of platform users. In 2020, Airbnb described tensions between protecting the privacy of hosts versus guests. They described the need to protect guests’ privacy, such as blocking hosts who might use hidden cameras in their properties to watch guests. One way they do this is through background checks of hosts. But Airbnb also noted that “the evolving regulatory landscape… in the data privacy space” may make it more difficult to perform background checks, and that hosts may feel like their privacy is being violated.

Other companies describe risks related to enterprise clients. In 2019, Salesforce noted that the responsibility of complying with the GDPR and CCPA extended to its enterprise customers. This increased business costs for providing education about the GDPR and CCPA to enterprise customers. The GDPR and CCPA could indirectly increase Salesforce’s exposure to legal liability, and also limited how Salesforce was able to use data originally collected by their enterprise customers.

Across this framing of business risk, companies related the legislation to the different ecosystems of stakeholders they interact with, suggesting how evolving privacy legislation may create new challenges and risks when addressing the needs of these different groups.

Discussion

In the paper we discuss what can we learn about privacy from SEC filings? First, it’s really interesting that companies frame privacy and data protection laws as posing more than direct regulatory risks. There’s a lot of indirect effects that they cite with these laws, like the reputational risks, which helps us to start think about these kinds of secondary effects of technology law. We also summarize how SEC filings provide insight into company practices related to privacy, and how we can think about privacy in ways beyond a user-centered discourse. We also argue that if we think about privacy laws and financial investment as infrastructures, that can enable new types of action for privacy advocates, practitioners, designers, and researchers – I’ll spend the rest of post focusing on those.

For privacy practitioners and advocates within companies, this might help provide workers with rhetoric and forms of argumentation that might allow them to better advocate for privacy reform in ways that are legible and actionable for managers and executives. A user-centered argument to advance privacy interests may not convince a corporate decision-maker. But perhaps tactically utilizing business risk language that aligns with a company’s statements to investors might go further, such as framing steps to address privacy as “a way to avoid regulatory and reputational risks,” rather than as being “good for the user.”

For designers, I think there’s a couple interesting design directions from this work too. In some other work I’ve done analyzing AI ethics toolkits, we find that ethical design tools often don’t have much advice about how to actually convince managers and decision-makers about why they should take the time and resources to address these issues. The rhetorical framings from this project might be helpful when designing new privacy and ethics tools, that can connect user-centered concerns that designers care about, to framings of business risk that may be more familiar and legible to organizational decision-makers.

I also think that the Form 10-K document could be really interesting source material for creating speculative design and design fiction. These documents try to convey potential future business risks through text – but what might we be able to learn, explore, or critique if we tried to represent the future worlds suggested by these risks through design artifacts? For instance, what could a future world look like where online behavioral advertising is no longer a profitable business model?

For researchers, I want to come back to this idea that financial investment can be a place for social values to be contested. Drawing attention to the discourses and practices of investment opens up new sites for studying how institutions are shaped.

There are existing practices try to create ethics and values-oriented change through investment, such as activist shareholding, where investors use their stake in a company to try to shape management’s decisions. This has been successful in shaping how companies disclose climate change risks and in shifting Apple’s and Microsoft’s practices regarding the right to repair. Researchers and advocates might work with existing activist shareholder groups, or work to convince large institutional shareholders to reconsider how they evaluate privacy-related risks in the companies they invest in. For instance, major large institutional investors have made recent statements that they will make investment decisions in part based on companies’ environmental sustainability practices, often called environmental, social, and governance investing or ESG. What might it take for institutional investors to view issues of digital privacy as important enough to consider as they make ESG investment decisions? Existing practices of voluntary ESG reporting, governance reporting, and human rights transparency reports with oversight from civil society organizations might play a useful role here. More broadly, we might think of new legal and regulatory regimes around data, and financial investment—and enact some of these things that companies might be concerned about.

I acknowledge a lot of these implications mostly work within existing systems of financial capital, rather than more radical forms of change, and I personally often have a healthy skepticism of market-based solutions for social problems. But given that so many tech ethics problems are created by investor demands or economic incentives, I think that at least in the short term, these perspectives and tactics can play a useful role in re-imagining more ethical forms of financial investment practices that might re-shape the social values promoted in the development of new technologies.

Paper citation:

Richmond Y. Wong, Andrew Chong, and R. Cooper Aspegren. 2023. Privacy Legislation as Business Risks: How GDPR and CCPA are Represented in Technology Companies’ Investment Risk Disclosures. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 7, CSCW1, Article 82 (April 2023), 26 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579515