This post by Richmond Wong summarizes the 2023 paper “Broadening Privacy and Surveillance: Eliciting Interconnected Values with a Scenarios Workbook on Smart Home Cameras,” by Richmond Y. Wong, Jason Caleb Valdez, Ashten Alexander, Ariel Chiang, Olivia Quesada, and James Pierce, published in the Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’23). [Download the full paper]

People are increasingly using smart home cameras. While these provide new ways to live and interact, they also present concerns related to privacy. In this paper, we created speculative scenarios to explore how smart home cameras might lead to surveillance by “primary users” who control the cameras, towards “non-primary users” who don’t. We used the scenarios in a values elicitation activity. While we were expecting people to mainly talk about privacy and surveillance, we found that participants reflected on multiple conceptions of privacy and connected it to other social values in complex ways. From these findings, we conclude that if we focus on privacy as the primary ethical issue to solve in smart home research, we may risk missing other important dynamics. Thus we suggest the need to broaden our conceptions of privacy when doing smart home research. Additionally, the paper provides a case study of doing research with primary and non-primary users.

In a lot of privacy research (and in data privacy law), we often focus on the relationship between individual users and the companies who collect their data, or between “data subjects” and “data controllers.” However, these perspectives often assume that users are pretty similar, and obscures how privacy can be experienced differently by different users, such as users who belong to vulnerable populations. Users’ social relationships with each other can affect their experiences of privacy, especially when they have different amounts of social power.

We distinguish between primary users (those who have more control and access to smarthome devices, often by owning them) and non-primary users (who have less control over these devices). This builds on prior smart home privacy research that has looked different types of relationships that users have with each other and their devices. Non-primary users may experience exacerbated privacy violations. They may lack access to the actual device, and may not have the social power to push back against a primary user’s practices.

Designing Scenarios

Our scenarios focus on 3 primary and non-primary user relationships: parents & children; landlords & tenants; and residents & domestic workers.

Through an iterative design process in 2021, we ended up with 9 scenarios about smart home camera privacy and surveillance, with 3 scenarios for each of the 3 relationships. There were a few design considerations we made in designing the scenarios:

- First, we tried to make sure the scenarios were not completely dystopian or utopian, but rather more ambiguous. So we tried to include aspects in each scenario that we felt were both positive and negative (at least from our perspective).

- Second, we made the scenarios take place in a near future, rather than a far-off future, as we thought it might be more relatable to participants.

- Third, while we played with different forms of text, images, and storyboards to represent the scenarios, we ended up constraining each scenario to a single sketch with captions, so that we could more easily show participants multiple scenarios.

- Fourth, we decided to create scenarios that appeared to be fairly regular and commonplace within their imagined world in order to prompt judgements about possible “new normals” (rather than depicting extraordinary events).

Below are 3 example scenarios we created:

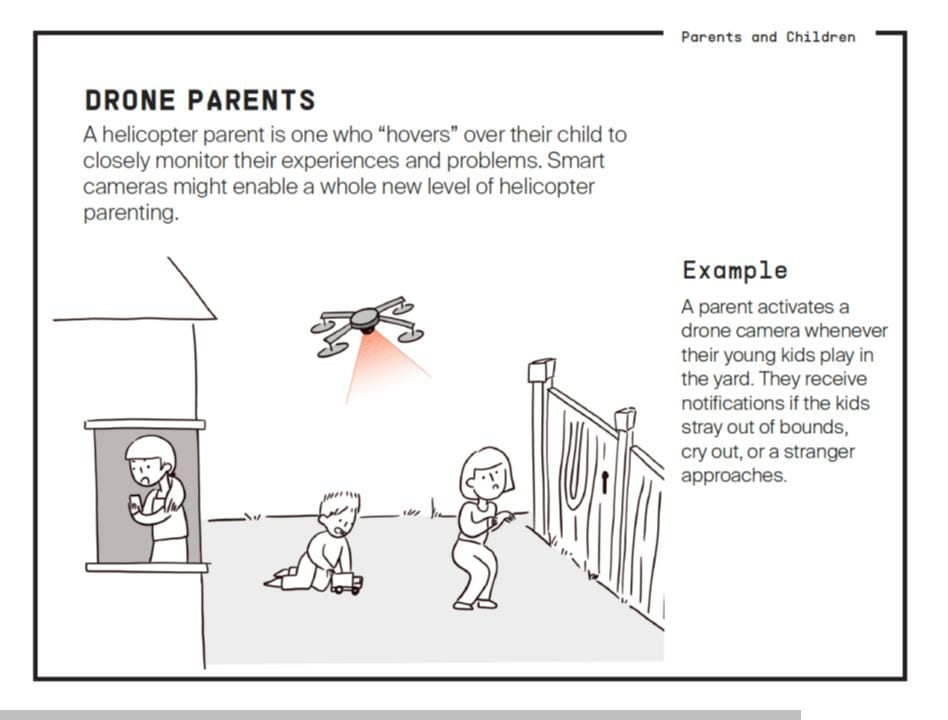

One scenario depicting Parents & Children is the “Drone parent”, which is a play on the term “helicopter parent”, or someone who metaphorically hovers over their child to monitor them. In the scenario, smart cameras attached to a drone make this literal. A drone camera watches children playing in a yard, and notifies the parent if the children stray out of bounds.

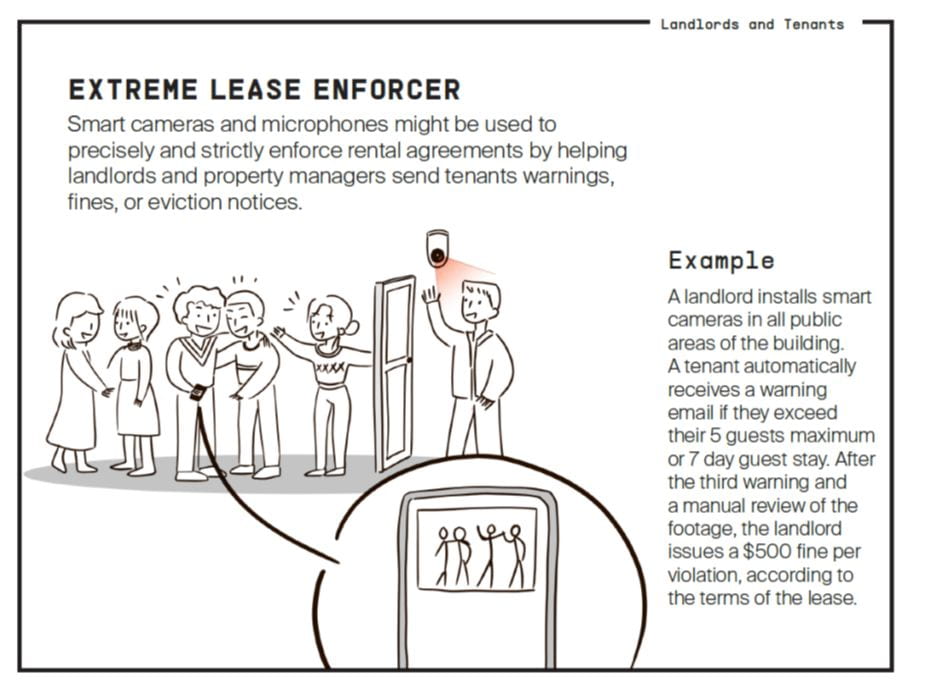

A scenario for Landlords & Tenants is the “Extreme Lease Enforcer,” where smart cameras and microphones more precisely and strictly enforce the terms of rental agreements—such as the number of guests a tenant is allowed to have, or making sure noise stays below a certain level. And the system can then automatically warn or fine tenants who violate those rules.

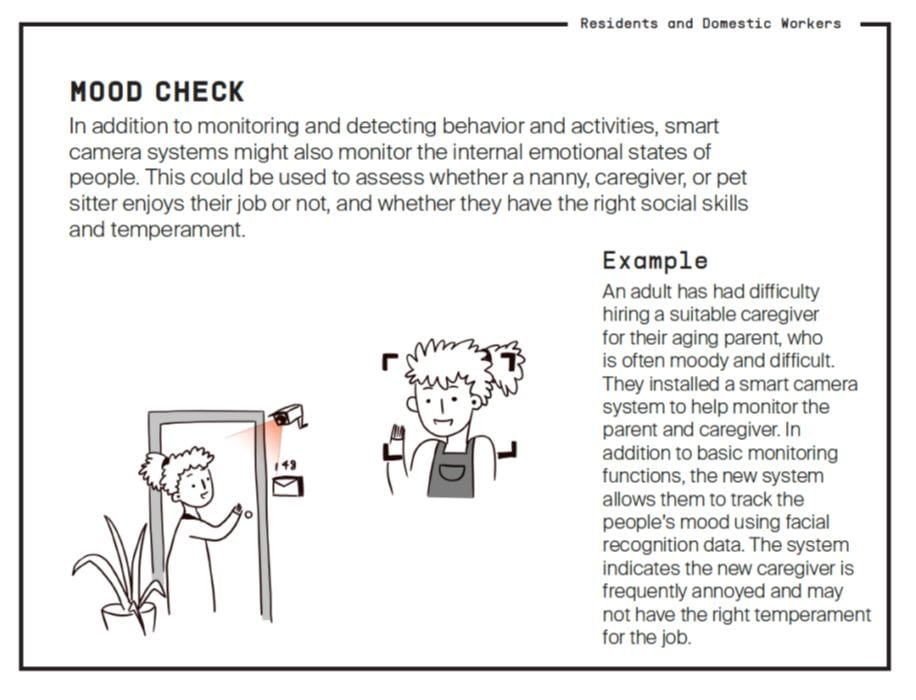

A scenario for Residents & Domestic workers is “Mood Check,” which attempts to use a smart camera to detect the emotional state of a nanny, babysitter, or caregiver to evaluate whether they have the right temperament for the job.

After designing these scenarios, we wanted to understand: When using these scenarios as elicitation tools, how do participants assess values and ethics? What are their perspectives, opinions, preferences, and judgments?

Through interviews, we shared the scenarios with 14 smart home technology users who fit into one or more of these primary or non-primary user categories of being a parent, child, landlord, tenant, home resident, or domestic worker (either currently or previously). Participants were over 18 and lived in the US. We never explicitly prompted participants to speak about specific social values, and did not mention privacy or surveillance when introducing the scenarios.

Our main findings are that participants highlighted a much broader range of values than we had initially considered. Yes they discussed privacy and surveillance, but they also discussed: autonomy and agency; physical safety and care; private property interests; trust and accountability in social relationships; fairness; and reflections on how users’ social identities affect their experiences. We’ll focus on just a couple of these in the blog post, but a takeaway here is that participants rarely thought about the scenarios in terms of a single value, but instead suggested interrelated values and concerns.

Autonomy and Agency

Participants referenced the need for users’ autonomy and agency. Several felt that the scenarios violated the autonomy of non-primary users across the scenarios. Several described how kids need to be able to “make mistakes” and “be themselves” without their parents watching to learn autonomy. P4 contrasted the scenarios with his own childhood, describing how his parents could only use a landline phone to check in on him when he was a younger. He felt that this setup gave him more autonomy than the scenarios’ always-on smart camera.

I’ll note that several participants re-imagined the scenarios to try to give non-primary users more agency and autonomy. For instance, P1 felt that the scenarios infringed on the agency of domestic workers, so she re-imagined a scenario where babysitters could use the cameras to monitor the family they’re working for, flipping the power dynamic.

Physical Safety and Care

Second, participants discussed the values of physical safety and care, which usually came up when participants felt positively about the scenarios. This came up most often in the parent and children scenarios. P6, a parent, said:

I can see where kids or teenagers might really hate that. But as a parent myself, I really like that[…]. You want to give them some semblance of privacy, but if you learn or hear that things are going wrong you can check in and make sure.

While recognizing potential privacy concerns, several participants felt that surveilling children’s activities was justified in order to care for their physical safety and security. I’ll note that privacy researchers Luke Stark and Karen Levy argue that even if surveillance as a form of care is socially accepted, these practices can still reinforce problematic power dynamics, and obscure other, less-surveillant forms of care.

Private Property Rights

Third, really interestingly, people’s beliefs about private property and land, and what power that gives a property owner in a US context, came up several times, particularly in the landlord-tenant scenarios. P6, a former renter, said:

If it’s in the rental agreement, I don’t see an issue with having something like this. A lot of people probably wouldn’t like it just because they feel like it’s invading their privacy. But it is the landlord’s property.

This suggests a belief that property ownership means that the landlord’s interests outweighs the tenants’ interests. Some also said this to justify parents’ surveillance of children: that parents own the home, and thus have the authority to control that space how they wish. These reactions give property owners, who are primary users in our scenarios, the leeway to do what they want.

However a few participants, particularly those with landlord experience, noted that in practice, landlords do not always have or use absolute authority. P9, who has landlord and property management experience, describes how the Extreme Lease Enforcer scenario changes the landlord-tenant relationship in significant ways, even though it says it just enforces the terms of a lease:

I’ve been a landlord and this crosses the line. Most rental agreements […] they’re loosely enforced. If someone has a guest for an extra week or so it’s not that big a deal. […] To me this is really micromanaging your tenants.

In practice, rules may be loosely enforced, even if technically prohibited. The Extreme Lease Enforcer scenario would change this by providing less leeway than what is socially expected. Overall, participants’ varying reactions highlight tensions in considering how to balance rights, social power, and control between private property owners and other stakeholders.

Takeaways: The Interconnectedness of Values

The paper reflects on several issues and provides implications for smart home design and research, including: describing how participants engaged with the scenarios to lead to values reflections; and the fluidity between primary and non-primary users (a person can be a primary user at one time and place, and a non-primary user at another). But in this post, I’ll focus on the interconnectedness of values.

Overall, participants surfaced reflections on a lot of values: privacy, autonomy, physical safety and care, property rights, trust and accountability, fairness, differences across social identities. One thing we debated as a research team is whether participants were discussing different conceptions of privacy, or different values?

And I think the answer is yes to both! Privacy scholars have discussed how there is no single definition of privacy—it’s multifaceted, and what privacy means is different in different situations. Sometimes, privacy might be about protecting autonomy. At other times, expectations of privacy are tied to property rights. Privacy is complex! And while this complexity is acknowledged and cited within HCI, practically, privacy is often operationalized in narrower ways within HCI research – Nora McDonald and Andrea Forte describe how HCI tends to conceptualize privacy as either being about an individual’s control over information, or as a set of community social norms.

I think there’s some important reflections we had in how we approached our interviews. First, by not constraining ourselves to a specific definition of privacy in our interviews, we were able to elicit reflections on a lot of different, complex conceptions of privacy, beyond control over information or social norms. Second, by not constraining our interviews to being just about privacy, we also surfaced a lot of interconnected values related to privacy. Sometimes these were tensions (surveillance as care violates others’ privacy). Other times they aligned (like privacy helps promote children’s autonomy). Third, our primary/non-primary user scenarios helped surface reflections on how privacy might be viewed differently among stakeholders with different amounts of social power. If we had explicitly focused our interviews around privacy as a form of information disclosure, we may have missed the wider range of concerns and values that our participants surfaced, and how they tied these values together.

Thus we suggest that researchers consider privacy in the smart home not as being an isolated goal to design for, but rather conceptualize privacy as inherently entangled and interconnected with other social values. Practically of course, a project may need to define its scope of investigation – but even when smart home research is conducted on a specific value like privacy, we suggest that designers and researchers should remain open to additional values that participants may surface, and create opportunities to bring these into the conversation.